Since it’s creation back in 1999, OSGi has evolved a lot. I haven’t seen much content about it around. Since it’s often appearing to me (AEM CMS, Apache Sling and now on Apache Felix) I decided to create this post. Here I will try to cover the basics about Open Services Gateway Initiative (OSGi) and show a practical example of how to create modular applications using Apache Felix OSGi container.

What’s OSGi?

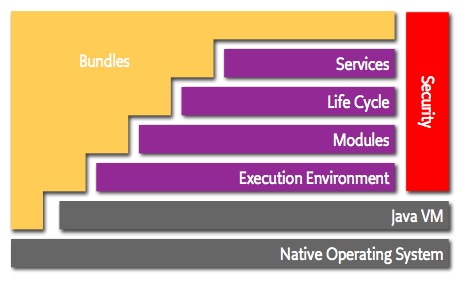

Basically, the OSGi defines an architecture for developing modular Java applications. OSGi specification describes a dynamic component model that allows applications and components, coming in form of bundles, to be started, stopped and updated without requiring a reboot.

A bundle can be understood as a group of classes that will become a single JAR, so it can be easily managed individually. Bundles contain additional resources defined in a detailed manifest file named MANIFEST.MF. This bundle file contains: Bundle name, description, version, exported packages (those contained in this bundle that will be available to the outside world), imported packages (packages that will be required from whoever use this bundle).

When talking about OSGi, services are in the layer that connects bundles in a dynamic way by offering a publish-find-bind model for plain old Java objects. A bundle can create a service and register it with the OSGi service registry under one or more interfaces, then any bundle that needs a service can go to the registry and ask for all available services. Services are dynamic. This means that a bundle can decide to withdraw a service from the registry while other bundles are still using it. OGSi containers such as Apache Felix, Equinox and Concierge provides a service registry that allows bundles to detect the addition or removal of new services on the fly, so it can adapt accordingly as we will see.

Life-cycle is the API defined to install, uninstall, start and stop bundles.

The modules layer of OSGi architecture is actually about keeping things local and not sharing. OSGi bundles are plain old JARs and, as we know, in normal Java everything in a JAR is completely visible to all other JARs. In OSGi, by default, there is no sharing. OSGi hides everything unless it is explicitly exported. A bundle that wants to use another JAR must import the parts it needs. Since the service model is about bundles that collaborate, the module concept exists to provide its dynamic behavior.

OSGi applications has an execution environment quite different from standard Java applications that usually runs on application containers. Bundles are deployed on an OSGi framework, that is, a bundle runtime environment. The framework uses the explicit imports and exports to wire up all bundles with its dependencies, so they do not have to concern about class loading. A simple API allows bundles to be installed, uninstalled, started and stopped on the fly. Since there is an API to do bundle management, each OSGi application can implement its own management system according to its particular needs. As we are seeing, most of OSGi’s features can be used in customized ways because of its huge concern on modularity. Having well defined boundaries for each of its architecture layers makes attractive for us to dig into it and build things in a way that works better for your context/project.

When beginning the initiative, OSGi creators wanted an application to emerge from the collection of different reusable components that had no a-priori knowledge of each other. They wanted it to emerge from the dynamic assembly of these components. An interesting way they found to achieve this was to provide a component system where developers could build components that can be added and removed independently, without affecting any other operation behavior. For example: you have a banking system that is capable of managing your account and your money. A component could allow users to check their account information using a web page. Another component could allow them to perform money transactions using an app. So these two components can be develop, added and removed without affecting any other function.

OSGi x microservices

If some of the OSGi aspects seems very similar to microservices for you: don’t worry. Many people get this feeling when starting to study OSGi.

The principle of OSGi services is to provide communication between modules through a well defined API. Since an API is (at least it should be) independent of the implementation, anyone can change one module without affecting the other. With web micro services the principle is the same but communication happens thought an endpoint like host:port/resource. The API can be defined however you want: informally or with something like Swagger (OpenAPI). Although OSGi and microservices share the same architectural style, they differ in their granularity. OSGI is an application architecture, while microservices is a distributed systems concept.

OSGi allows you not only to defer the decision to support microservices, it also allows you to add microservices to your system afterwards. Therefore, in a context of web microservices built using OSGi our microservrices would be the highest abstraction level, and OSGi services inside bundles would be something like “nanoservices”, since it can also be shared with bundles from other microservices. Just like individual microservices, OSGi services/components are easy to deploy, test, and maintain. Language agnosticism is actually a limitation of OSGi, so different from a microservices architecture where you can have any programming language, OSGi is only supported by the JVM.

Here is a good post discussing specifically microservices in OSGi context.

Creating an OSGi application

Let’s create a simple OSGi application with some bundles to see how it works by practicing. Here I’ve used Apache Felix, a very well know OSGi container that is widely used.

First, a nice plugin to have installed is bndTools. It’s a IDE plugin that helps us to create and manage OSGi application inside modern IDEs. If you’re using eclipse you can just search in Eclipses’ marketplace “bndTools”, or take a look at its installing steps.

We will build a sample application composed by 2 different bundles: an API and a component as the following diagram shows:

- The API bundle will export a service interface,

Billing. - The Provider bundle will import the interface and publish an instance of the service.

The complete source code can be found on: https://github.com/andreybleme/discovering-OSGi

Creating the API bundle

This is a standard Java Project with some additional configuration files for constructing OSGi bundles.

-

From your file explorer, select new > BndTools OSGi Project.

-

Type ‘org.store.api’ as the project name. You must use a Java versions equal or superior to 1.5.

-

When you are offered for using a project template to start the project, choose “empty project”.

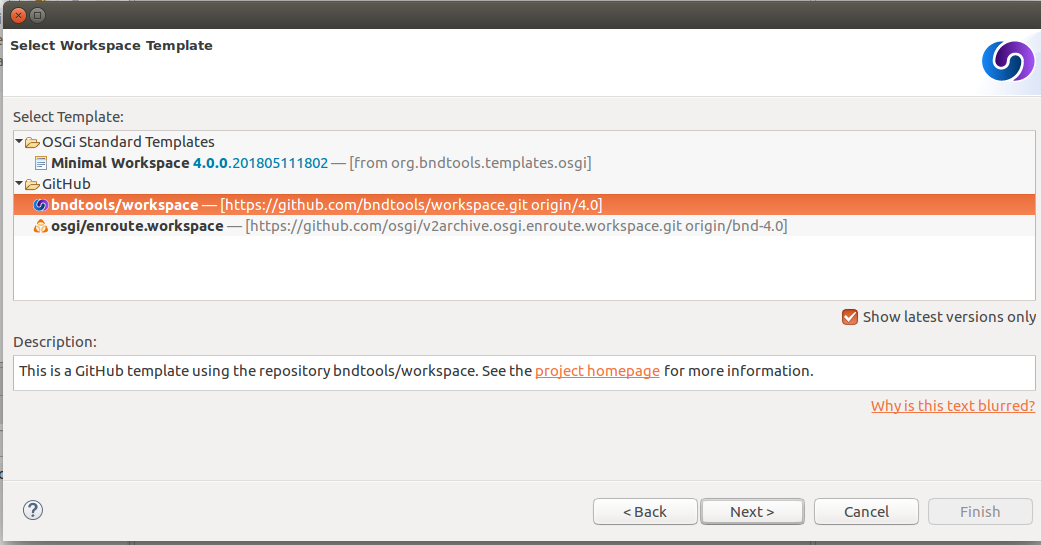

Since this is the first time you are using bndtools in your workspace, you will see the “Welcome” dialog. Click “next” followed by “finish” to allow bndtools to setup a configuration project and import a basic repository. A repository is a place where bundles that you use in your projects are stored. A remote bndTools repository is created by default and it contains some often used bundles.

When creating the workspace thought the welcome dialog, do not choose the option “Minimal Workspace”. The option we need to use is “bndtools/workspace” because of a known issue about some dependencies.

After you crated the empty project and the bndtools workspace, a folder named cnf was created containing workspace-wide configuration to be shared between different bundles we are going to create. Another important point to notice: a bnd.bnd file was created at the top of the bndtools project containing project settings.

Now let’s create a fairly trivial API: In the src directory of the new project, create a package named org.store.api. In the new package create a Java interface named Billing, as follows:

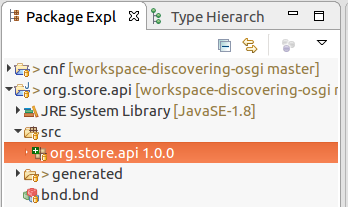

The project we have created defines a single bundle with a Bundle Symbolic Name (BSN) of org.store.api (the same as the project name). As soon as we created the project, a JAR named org.store.api.jar was created in the generated directory, and it will be rebuilt every time we change the bundle definition or its source code.

However, the bundle is currently empty, because we have not defined any Java packages to include in the bundle. This is an important difference of bndtools with respect to other tools: bundles are always empty until we explicitly add some content. You can verify this by double-clicking the bundle file and viewing its contents: it will only have an META-INF/MANIFEST.MF entry.

Configuring the bundle

In order to add the package org.store.api to the exported packages of the bundle: open the bnd.bnd file at the top of the project and select the Contents tab. Now the package can be added in one of two ways:

- Click the “+” icon in the header of the Export Packages section, then select org.store.api from the dialog and click OK. Or…

- Enter Export-Package: org.store.api manually in the Source tab.

As soon as this is done, a popup dialog appears titled “Missing Package Info”. This dialog is related to package versioning: it is asking us to declare the version of this exported package. Click OK.

Save the file, and the bundle will be rebuilt to include the selected export. We can confirm by opening the Imports/Exports view and selecting the bundle file in the Package Explorer. Note the package has been assigned version 1.0.0:

Creating the provider (implementation) bundle

Create another project, named org.store.impls. At the Project Templates step, select Component Development (Declarative Services) and click Finish.

In order to add the API project as a build-time dependency of this new project, open the bnd.bnd file of the newly created project Click the Build tab and add org.store.api by clicking the “+” icon in the toolbar of the Build Path panel. Double-click org.store.api under “Workspace” in the resulting dialog. It will move over to the right-hand side then click Finish. Now the org.store.api bundle will appear in the Build Path panel with the version annotation “latest”.

We will create a class that implements the Billing interface. When the project was created from the template, Java source for a class named org.store.Example was generated. Open this file and make it implement Billing:

Here we used the @Component annotation to enable our bundle to use OSGi Declarative Services to declare the API implementation class. This means that instances of the class will be automatically created and registered with the OSGi service registry.

We can (and should) write a test case to ensure the implementation class works as expected. In the test folder, a test case class already exists named org.store.ExampleTest. Write a test method as follows:

Configuring the bundle

As in the previous bundle, it is automatically built based on the content of bnd.bnd. In the current project however, we want to build two separate bundles. To achieve this we need to enable a feature called “sub-bundles”.

Right-click on the project org.store.impls and select New > Bundle Descriptor. In the resulting dialog, type the name provider and click Finish.

A popup dialog will ask whether to enable sub-bundles. Click OK.

Some settings will be moved from bnd.bnd into the new provider.bnd file. You should now find a bundle in generated named org.store.impls.provider.jar which contains the org.store package.

We’d now like to run OSGi. To do so we need to create a “Run Descriptor” that defines the collection of bundles to run, along with some other run-time settings.

Right-click on the project org.store.impls and select New > Run Descriptor. In the resulting dialog, enter run as the file name and click Next. The next page of the dialog asks us to select a template: choose Apache Felix 4 with Gogo Shell and click Finish.

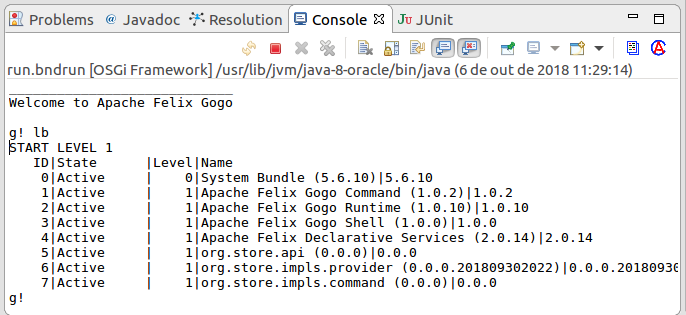

In the editor for the new run.bndrun file, click on Run OSGi near the top-right corner. Shortly, the Felix Shell prompt “g! ” will appear in the Console view. Type the lb command to view the list of bundles.

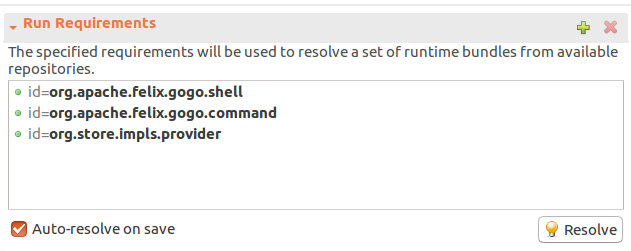

Now we want to include the org.store.impls.provider and osgi.cmpn bundles. This can be done as follows:

- Click the “+” icon in the toolbar of the Run Requirements panel to open the ‘Add Bundle Requirement’ dialog.

- Under “Workspace”, double-click

org.store.impls.provider. - Under “Bndtools Hub”, double-click

osgi.cmpn. - Click Finish.

The Run Requirements panel should now look like this:

Check Auto-resolve on save and then save the file. Returning to the Console view, type lb again:

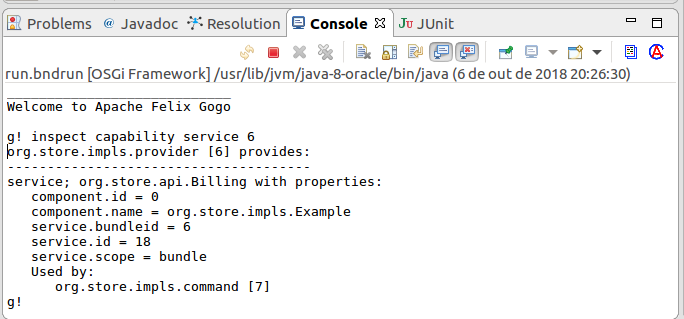

We can now look at the services published by our provider bundle using the command inspect capability service 6:

Our bundle now publishes a service under the Greeting interface.

The complete source code can be found on: https://github.com/andreybleme/discovering-OSGi

OSGi is powerful. It can be a pain in the neck when used on scenarios where a simple Spring application could solve your problem, since its containers are still a litle bureaucratic and its containers still suffer from a lack of convention over configuration mindset when compared to some modern technologies. Despite of that, it provides us a very mature modular architecture that allows us to create adaptable and dynamic tools.

I strongly suggest you to go on and try some technologies built on top of OSGi to see how smooth can be modularity.