When we think of the speed in which we are able to deliver software, it seems to be always related to the quality and the correctness. We want to be able to deliver software into production fast, and always being sure that it meets the quality standards so our customers are happy. Of course, we know that this is not easy to achieve given the complexity of systems we use to be working on. To be able to achieve and sustain a fast flow of work from Development into Production (Operations), we need to reduce the risk associated with deploying and releasing changes into the production environment.

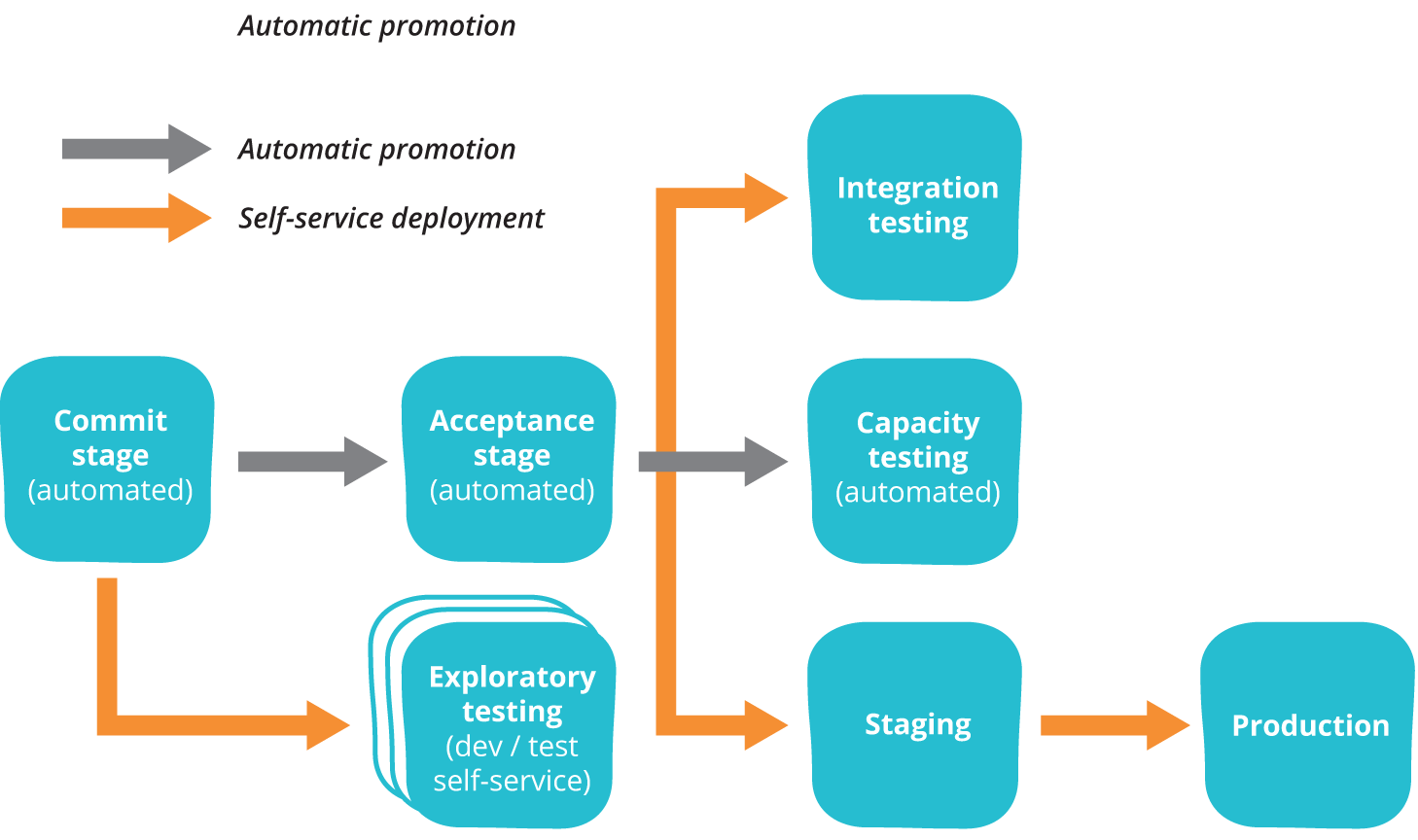

Image source: The Deployment Pipeline, by Martin Fowler

At this second post of The DevOps Journey series, I will elaborate on how to achieve this by focusing on implementing a set of technical practices known as continuous delivery. At the end of this article, you will be capable of understanding how to create the foundations of your deployment pipeline, to ensure that you are not entering the chaos by having automated tests that constantly validates that we are in a deployable state allowing developers to integrate code into trunk every day, therefore reducing the lead time to get production-ready code, and getting fast feedback while making people more productive.

The foundations of a deployment pipeline

To achieve a fast and reliable flow from Dev to Ops, we must ensure that we are always using production-like environments to validate our work. It does not matter how many times we have double-checked our work using an environment that is not similar to the one in which the system is going to be executed for customers. We often discover problems only when customers report them, and this is what we want to avoid.

To do so, we need our production-like environments to be easily created on-demand, by running automated tasks (scripts). This enables developers to quickly create these dev/stage/prod environments as they need, to validate work before it reaches customers. Developers are lazy (as they should be), and if somehow the process of creating a new environment requires manual work, too many people approval and bureaucracy, they will simply try as hard as possible to avoid testing their own work on a production-like environment.

Among the many available tools that provide us the capability of easily creating these virtual environments, I can highlight: Terraform, Ansible, and Docker. It’s a common approach to use Infrastructure as a Code tools (Terraform/Ansible) to define the configurations of our environments, and provision Docker containers to run applications. This setup will definitely help you to achieve a fast way to create and execute on-demand environments that will work as pre-production for both developers and people from Ops. Everyone benefits from this practice: customers are going to be less frequently surprised with errors, and developers won’t need to stay late fixing urgent bugs that were only found in the production environment.

Another very important aspect we want to achieve, is to make our infrastructure components easier to rebuild than to repair. Since we are already equipped with tools that allow us to define and provision our entire infrastructure as a code, we can fix a problem at any server by simply deleting it and recreating it again. If you are using Terraform, for example, this should be as easy as running two commands.

To destroy your infrastructure environment:

terraform destroy

After rewriting the configurations and fixing the existing problems:

terraform apply

By having repeatable environment creation systems, we are able to easily increase capacity by adding more servers into the rotation when needed, and of course, we increase our capacity to recover from disasters that result when we must restore services after some catastrophic failure of irreproducible infrastructure. To maintain the benefits of having these infra creation systems, we must always ensure the consistency of our environments, whenever we make production changes (applying patches, changing security rules and any kind of configuration) we must remember to apply this changes immediately in all our existing environments (dev and stage).

This practice we have discussed above has become known as immutable infrastructure, where manual changes to any of our environments are not allowed. The default way of handling changes at the infrastructure is to update code, push it into the source code management system, and run the automated scripts/commands that do the entire work.

Integrate tests into your pipeline

Now that we already have our solid foundation, everyone must be already using production-like environments in their daily work, integrating and running code for every new feature. After having this, usually, organizations move into a step that consists of assigning QA engineers to start testing the entire deployed software to assure that everything meets the requirements. However, we are likely to get undesired outcomes from this practice: by finding and fixing errors in a separated phase only after all deployments were already completed, developers will learn about their mistakes only weeks or months after they introduced the given features that contain the errors. As expected, the time required to fix them will be way more significant, since developers will now need to perform some “archeology” work to remember how things work for a given piece of code. The relation between cause and effect is thus faded and the productivity goes away.

Automated testing can address this issue! If we can guarantee that we are always checking the health of our automated tests, we will be way more secure on deploying our code with fewer failures. A widely adopted practice to enable this is to integrate our automated tests into our deployment pipeline. Every single time we deploy code into any of our production-like environments, we should run our tests. When any developer commits code, it should automatically run against a suite of automated tests. If the code passes, it is automatically merged into trunk, and deployed into your configured environment (production or production-like). This process will result in a “Release on Green” philosophy, meaning that at any time of the day, we can make a release with the code deployed into one of our environments.

This enables a high-trust culture where people can detect and correct issues quickly, immediately after they have submitted the code to the given environment.

Strive for a reliable validation test suite

We must know what kinds of automated tests should run for our deployment pipeline.

When facing deadline pressures, developers may stop creating unit tests as part of their daily work. To detect this we must measure and make visible at our deployment pipeline the test coverage, and ideally set a limit for this coverage to be allowed (80% of all classes must include tests for example).

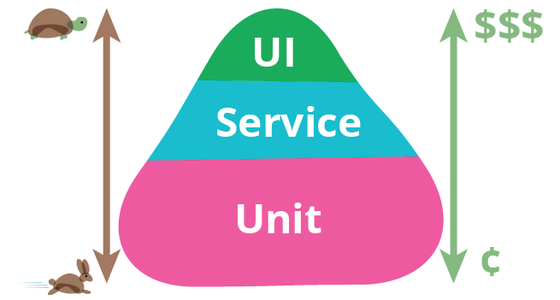

Remember that the goal of our automated test suit is to find errors as early as possible. So we must run the faster-running automated tests first, before the slower-running ones, which are all, of course, run before any manual testing.

Image source: Test Pyramid, by Martin Fowler

Wrapping up the requirements for a reliable validation integrated test suite:

-

Ensure that your tests run in parallel if necessary.

-

Avoid by all means any kind of exploratory and validation manual tests before the test step of your pipeline has passed.

-

Constantly revisit your test suit to make sure you are always running the fastest tests (unit tests) before the more expensive ones (integration, acceptance, and end-to-end tests).

-

Track the performance of your tests. The slower and error-prone your test suite, the lazier developers are going to become on creating new tests and worse, to fix existing broken ones.

Pull the Andon Cord when the pipeline fails

When our deployment pipeline is in a green state, it provides us a high degree of trust that the code is going to work as it was designed to work.

In order to keep our deployment pipeline in a healthy and always green state, we must create a virtual Andon Cord, similar to the ones used at production lines for car companies such as Toyota.

Image source: Andon Cords and Practice Environmentalism, by leanvets

Whenever someone introduces a change that causes our build or tests to fail, no new work should be allowed until it is fixed.

To build a high-trust DevOps culture, you should prioritize team goals over individual goals. If someone needs help to fix a problem at the deployment pipeline, they should be allowed to bring whoever they need to help to solve the problem as fast as possible and move their work forward.

The consequences of not pulling the Andon Cord and immediately fixing deployment pipeline problems are very familiar, but we still ignore it quite often:

-

Someone checks in code that is broken, and no one fixes it, because, well “it was already broken”.

-

Someone else checks in another change into a brand new build, that immediately starts to fail because of the existing problem that was not yet fixed. People at this stage will probably have no idea why their build is failing.

-

Our test suite will slowly get unreliable, and people will become very unlikely to build new tests. “We cannot even get the current tests to run, why should I build new ones?”.

Beware and make sure you are not wasting everyone’s time and money by not pulling the Andon cord when things go wrong. Remember: you have spent a considerable amount of time proposing and creating your deployment pipeline, make it worth!

Decouple the release from the deployment

The way that we use to think of a process of launching a software project, we take into consideration some date defined by the marketing team where the ops team performs a deployment the day before, and in the morning after we announce to the world what’s new on our product, enabling customers to use the given features. However, quite too often things don’t go according to the plan. We may experience production outages due to unexpected and never tested workloads, leading our software to fail both to customers and for the entire company. Restoring this in-production failing services may require a significant amount of work, that needs to be performed as soon as possible, making this a miserable experience for workers who are typically under a lot of pressure on this kind of situation. As long as these terrible situations keep happening, we tend to associate launching dates with periods of exhaustive work to solve unexpected problems, which is, of course, the opposite direction we need to follow: we want our team to be eager to launch small batches of work with as much frequency as possible.

To enable our team to keep striving for efficient and frequent deliveries, we must decouple our production deployments from our feature releases. In practice, the deployment and release of the word may be used interchangeably, but let’s elaborate a bit on the different purposes of these two events:

-

Deployment is the installation of a specified version of your software into a given environment. This deployment may ou may not be related to a release of a new feature for customers.

-

Release is when we make a feature, or a set of features available to our customers.

When we conflate the two different events, it can make it difficult to create accountability for successful outcomes. We need to separate and decouple these two activities, since we want to empower the development and ops teams to be responsible for the success of fast and frequent deployments, while the business outcomes of a given release may be a response from product owners. As we become able to deploy frequently and on-demand, how quickly we expose new functionality to customers is no longer a technical decision, but a business and marketing decision.

To make this a reality, we may pay attention to two categories of release patterns we can use: environment-based release patterns and Application-based release patterns.

Environment-based release patterns

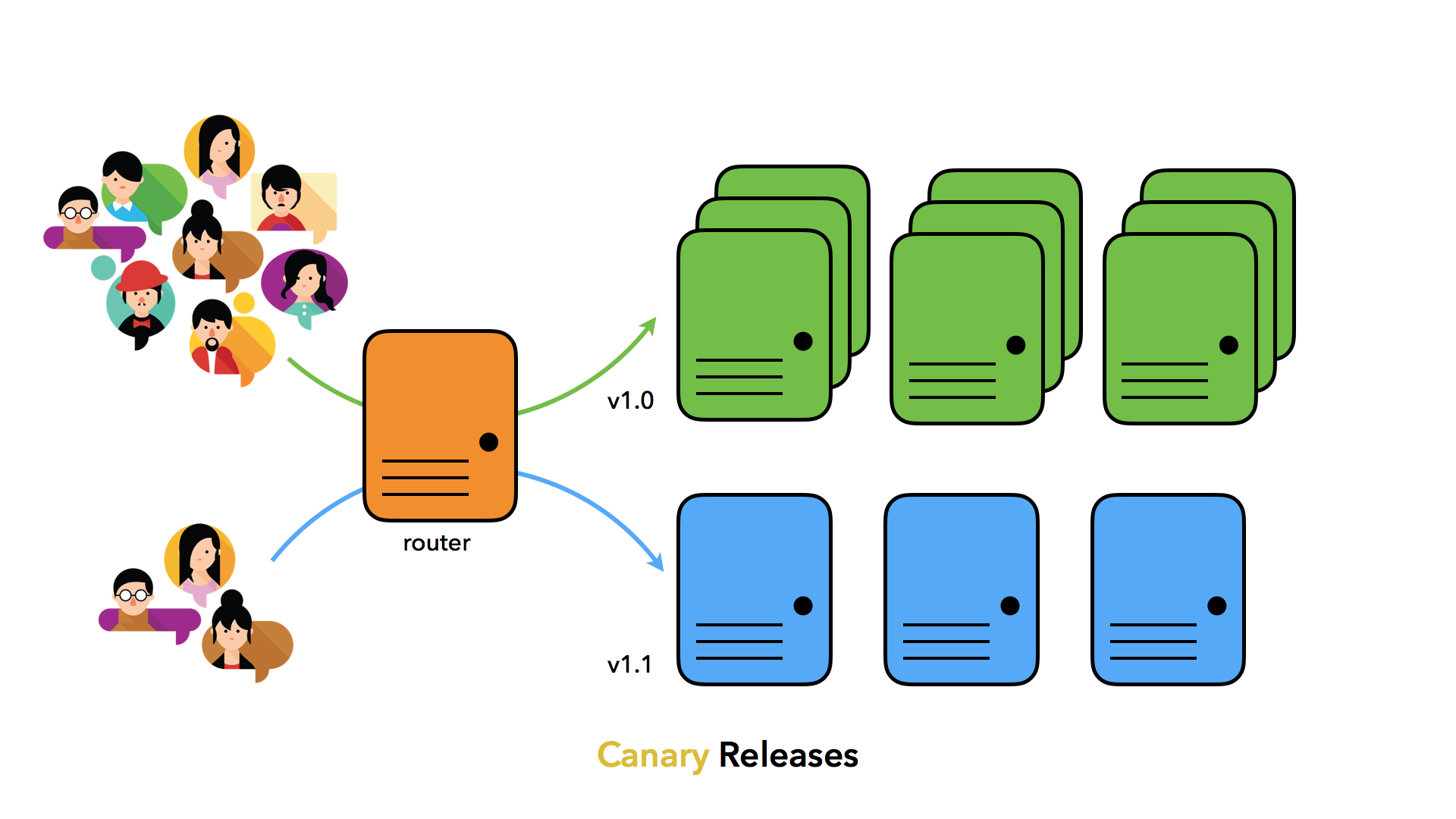

These are strategies where we have two or more environments that we deploy into, but only one of them receives production traffic from real customers. The new code is deployed first into a non-production environment, and the release is performed moving traffic to this environment. These kinds of patterns are very powerful and require little or no change to our existing application code.

As the most used release environment-based patterns are: blue-green deployments, canary releases and cluster immune systems.

Image source: Using Canary Release Pipelines to Achieve Continuous Testing, by Greg Sypolt

Application-based release patterns

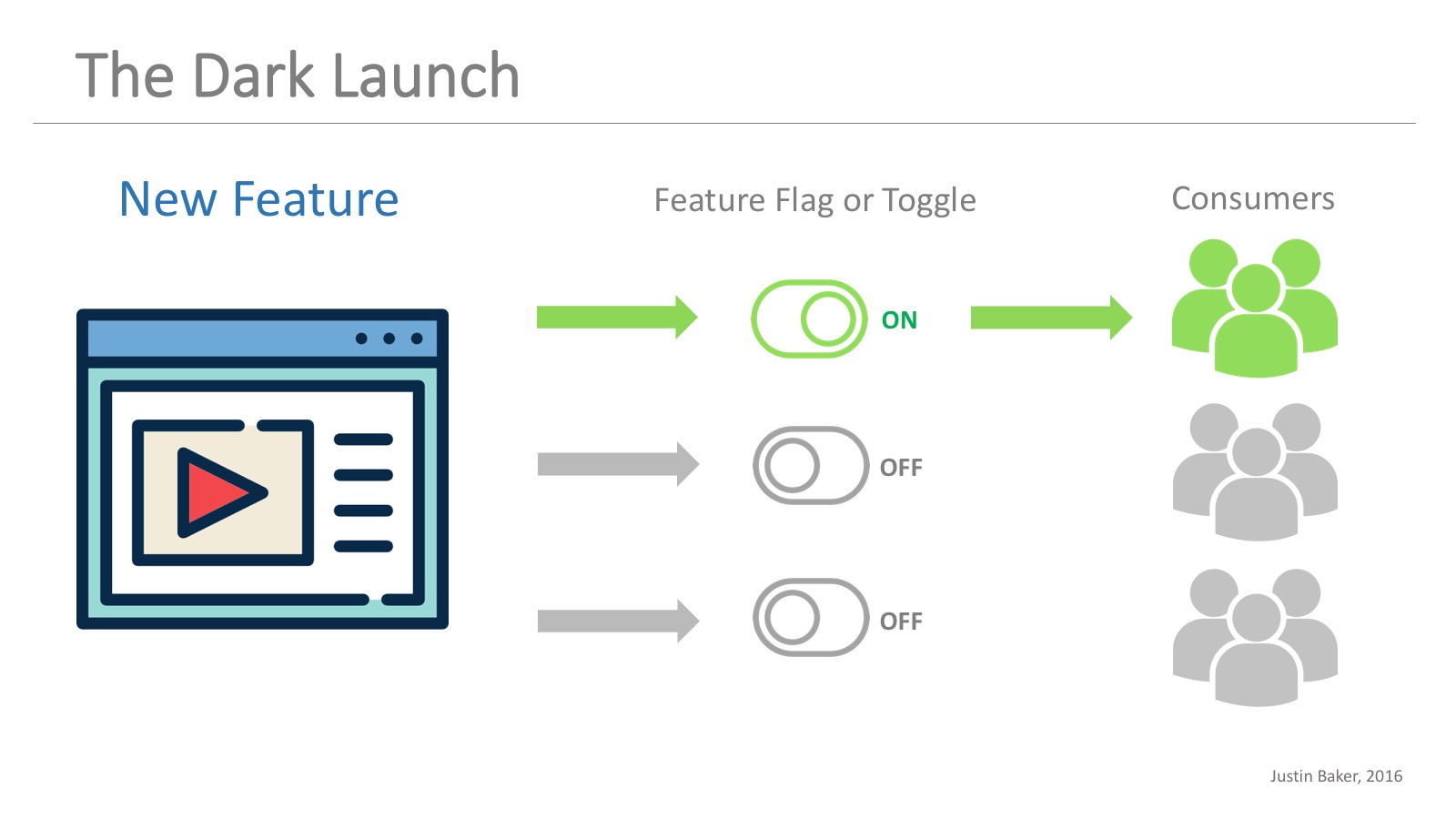

As the opposite of the environment-base release patterns, application-based release patterns require us to modify our application so that we can selectively release and expose specific functionalities by applying small configuration changes. We can implement feature flags to make a set of features visible only to a specific group of people, like internal employees, 1% of our customers, and so forth until we feel confident about releasing it to the entire user base. This enables a practice known as dark launch, where we can test a set of features with production traffic without actually releasing it. That was exactly what facebook made during their chat feature release in 2008!

Image source: Why Leading Companies Dark Launch, by Justin Baker

In this post, we have covered the main practices and principles we need to pay attention to if we want to enable the fast flow from Dev to Ops. If you make sure to always revisit these principles, you are on the right way to deliver quickly and safely to customers. There is a broad variety of tools we can use to help us on the journey, but remember to focus on the principles first, the motivation behind a new technology adoption, instead of blindly installing any “cool automation tool” and expect that it will help.

In the next post of our DevOps Journey series, we will see how to see problems in our software as they occur, and be able to react fast, before our customers are affected by adding telemetry and amplifying the feedback we receive from our system.

If you liked this post, consider sharing it.